| Language: |

INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES STANKIEVECH

Charles Stankievech (*1978, Canada) is an artist redefining "fieldwork" at the intersection of geopolitics, deep ecology, and sound resonance. His work spans from the northernmost settlement in the Arctic to the depths of the Pacific, uncovering the paradoxes of our existence on the planet by engaging with the imperceptible. Stankievech's interdisciplinary approach reveals hidden layers of reality through immersive installations and thought-provoking projects. He is a professor at the University of Toronto, where he continues to explore the boundaries of art and science. Stankievech's unique perspective challenges conventional views, offering profound insights into the unseen forces shaping our world.

Stankievech's latest book The Desert Turned to Glass published by Hatje Cantz, explores the collision of the cosmic and the chthonic. This richly illustrated volume, created to mark the centenary of the planetarium as an architectural form, gathers a new body of work that bridges cosmological visions from cave art to modern planetarium technology, exploring alternative theories on the origins of life, consciousness, and art.

Charles Stankievech: The Eye of Silence, 2023. 6K video 30mins with 7.1 audio. Installation View at Contemporary Calgary Planetarium Dome. © Studio Stankievech

In conversation with Hatje Cantz, Charles Stankievech explains how his book project was inspired by the hundredth anniversary of the planetarium, linking ancient and modern representations of the cosmos, from Palaeolithic caves to contemporary dark matter research, reflecting on humanity’s evolving consciousness and the book’s thematic and design choices.

Hatje Cantz: The Desert Turned to Glass sounds like an exciting title that allows many interpretations. Could you tell us something about the inspiration and concepts behind this project?

Charles Stankievech: The Desert Turned to Glass was made for the hundredth anniversary of the planetarium, which allows us to take stock of one of the most important architectures of wonder. Such an architecture is part of an archetype that began with Palaeolithic caves as the first representations of the cosmos, evolving into spiritual temples such as the Parthenon, then medieval cathedrals and mosques, and finally into the modernist planetarium. I feel there is something about the darkened dome space that fosters an engagement with the world beyond our reach, whether shamans performing rituals in prehistoric caves or contemporary research of dark matter and black holes in subterranean labs outside Toronto where I’m based. As a volume, the book collects over a decade of my research on the development of our consciousness through deep time that first started while I was an artist-in-residence in Marfa, Texas, reflecting on the surrounding desert landscape, where both meteorites and the first atomic explosion melted the desert sand into glass… and where the title of the book comes from. Fittingly, Walter Benjamin’s short text opens the book—and begins the conversations that are continued throughout the volume—by reflecting on humanity’s need for an ecstatic connection with the cosmos in the modern era of technological acceleration. His text was written circa 1923 as a response both to the first planetarium ever built and to the aftermath of World War I—modern humanity’s first planetary catastrophe…one that became a precedent both of future conflicts and environmental crisis. Today, in a moment where we are understandably obsessed with apocalyptic endings, I feel the book reflects upon our shared beginnings.

HC: Your publication, published by Hatje Cantz, stands out due to the strikingly elaborate graphic and even tactile design of the book. Can you tell us something about the process of creating the book? Did you know right from the start what the book should look like, or did this only emerge during the process?

CS: The pleasure of making a book versus all the other types of publishing today is its material existence, so creating something that engages the senses of the reader from cover to cover was extremely important. Working with Ala Roushan, one of the editors of the book, we knew from the beginning exactly what we wanted. The book was made while we were living in Japan as professors at the University of Tokyo, so there definitely was an influence from Japanese material culture and design. I also worked with the same graphic designer I often do, Raf Rennie, who has a strong dark aesthetic and scifi influence. He specifically designed the title typeface “Glass” just for this project. The book was definitely the result of a resonance of sensibility between us. The challenge working with such strong design is also making a document at the end of the day that is readable and draws the reader in, and this was important because, we had to navigate archiving a complex body of artwork as well as lot of texts by leading thinkers and scientists. We didn’t just want a stylish book that was illegible. It was essential we found the balance between pushing the design on the one hand, but on the other hand still supporting complex writing and space for the images to breathe. It’s also important to mention, treating the book as type of architecture, where there can be an exhibition within the pages, has always been the way I’ve approached making books—starting with my monograph LOVELAND, the inaugural book I designed for the press K. Verlag (which I co-founded in 2011 in order to publish the book). That book established the concept and the art direction of the press as a balance between critical thinking and using the unique structure of the book to exhibit art and visual culture. Instead of producing exhibition catalogues, I’ve tried to create a genre somewhere in between the artist book and a research volume. In the case of The Desert Turned to Glass, you can see such subtle design elements in how the dustjacket has a debossed meteorite, and then hidden underneath on the cover is a meteorite crater. Also, like I did in LOVELAND, I included facsimile reproductions of the first editions of J.G. Ballard’s climate fiction ‘World Trilogy’: pages-within-pages creating a material history of intertextuality.

Charles Stankievech: The Desert Turned to Glass, 2012/2023. Installation. Image credit: Studio Stankievech

HC: A special feature of The Desert Turned to Glass is definitely the dominance of the black colour. Can you tell us the background to this?

CS: We worked very hard with the team at Hatje Cantz to create a solid black tome! The body of work that the book archives is all about outer space and deep caves, so we wanted the ‘neutral’ background of the book to be as dark as possible. There was no white cube in the original exhibition, so why would we have default white pages? In a sense, we wanted the images and text to emerge out of the darkness and then to slip back into darkness—hence the cinematic fades opening and closing the book through progressively exposed images. One artwork in the book The Darkside of the Sun is an intense installation with a pool of 15,000 liters of oil, water and bacteria in a dark subterranean space that flows out of a deep cave. In the exhibition it takes about 5 mins for one’s eyes to become accustom to the lack of light in order to experience the piece.

Charles Stankievech: The Dark Side of the Sun, 2023. 15,000 litre reservoir, crude oil, bacteria (Alcanivorax Borkumensis), water, CO2, Rundle rock, geomembrane, submersible speakers playing infrasound. © Studio Stankievech

Echoing these ideas, we worked with a special black ink and printing process in order to get the blackest possible pages. Finally, this might sound strange when we are talking about a book for a publisher like Hatje Cantz, but the darkness in the book follows my suspicion of the visual. At the core the whole project is about the unknown—it’s about the invisible. In my lectures on the history of art and visual representations at the University of Toronto, I always talk about the importance of darkness for Upper Palaeolithic marks and drawings. Today we look in our textbooks and see the caves illuminated with flash photography and see full, rich colors of the mineral markings on the walls, laid out completely and very clearly. And, of course, an archaeologist or anthropologist wants to have as clear a picture as possible to do their analysis (I also made LiDAR scans of preshistoric caves in Namibia for this book), but in a certain sense, by illuminating the cave in such a bright manner and seeing everything, one actually doesn’t see what the creators saw, since they were originally sensing their environments in liminal light or darkness. And so, this idea of seeing more is not necessarily helpful for us to understand an embodied experience or embodied sense of culture. This is the argument for esoteric knowledge and the value of learning something within a set of practices, within a ritual, at a certain place, at a certain time, under certain tutelage, versus the fungibility of information as data. Instead of illumination, one must understand how images appear out of the darkness and how darkness actually creates an understanding of the world. This isn’t an argument for obfuscation. I’m actually talking about how the unknown and the darkness participate in this larger picture. It’s not an argument for ignorance, which is a kind of binary that the Enlightenment constructed: knowledge versus ignorance. Rather, I’m interested in how things emerge out of the darkness and descend into the darkness as a cycle, as an ongoing story.

The interview with Charles Stankievech was conducted by László Rupp in May 2024.

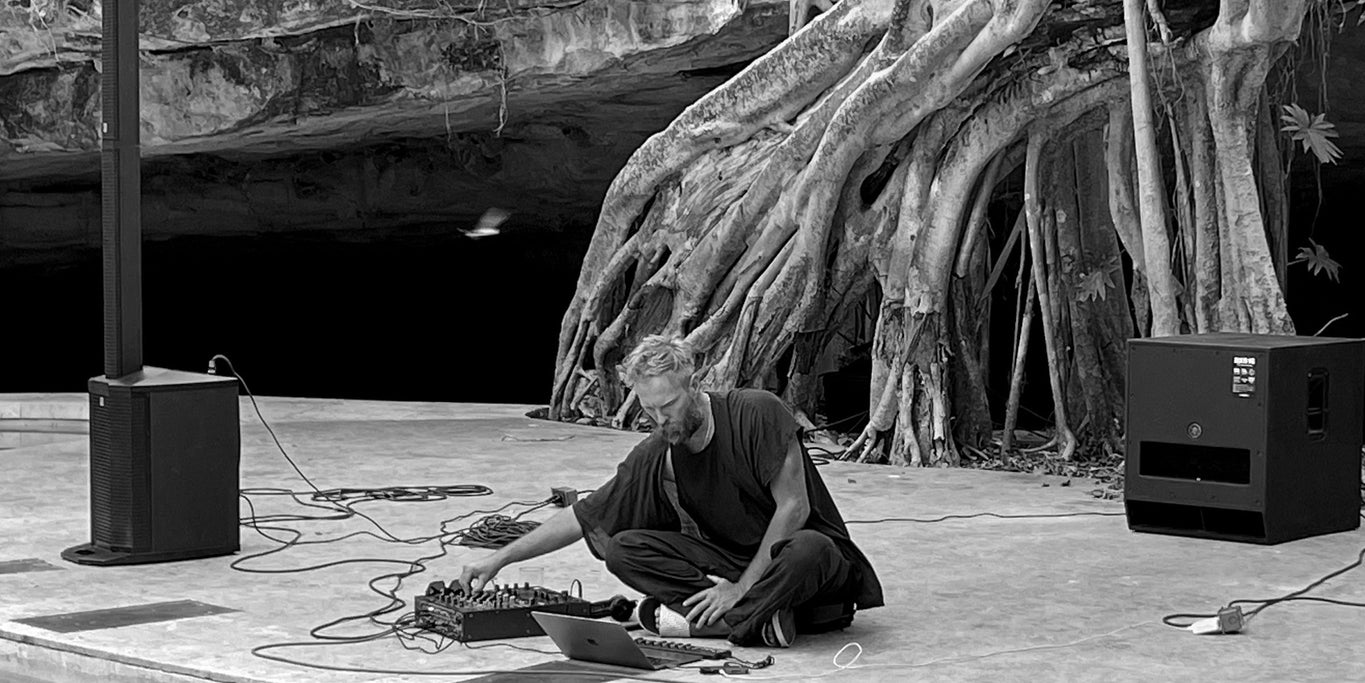

Header image: © Studio Stankievech